Lymphoma is one of the most common neoplasms in cats, and the most common anatomical form is alimentary lymphoma. Lymphoma can occur almost anywhere in the body; however, the cutaneous form is rare in cats [

1,

2]. It has been well studied in dogs but not in cats [

3]. Feline cutaneous lymphoma can be divided into epitheliotropic cutaneous lymphoma (ECL) and non-epitheliotropic cutaneous lymphoma (NECL). Most epitheliotropic tumors are of T-cell origin, and the tumor cells infiltrate the epidermis and adnexal epithelium in ECL [

3]; however, tumor cells are of either T-cell or B-cell origin and do not usually involve the adnexal gland in NECL [

4]. Previous studies have reported that the prognosis of NECL is grave, and its median survival time appears to be shorter than that of ECL [

3,

5]. Herein, we report a case to describe clinical and pathological findings of T-cell NECL in a cat.

An 11-year-old, spayed female Persian cat was referred to the Gyeongsang Animal Medical Center, Gyeongsang National University for skin lesions. The owner noticed a small crusting lesion on the dorsal neck 2 months before administration, and patches, plaques, and firm nodules were observed thereafter. Moderate pruritus, lethargy, and micturition disorders were also recorded upon systemic review. Bacterial and fungal culture tests of the skin lesions revealed no growth of pathogens, and the lesion was not responsive to antimicrobials from the local veterinary clinic.

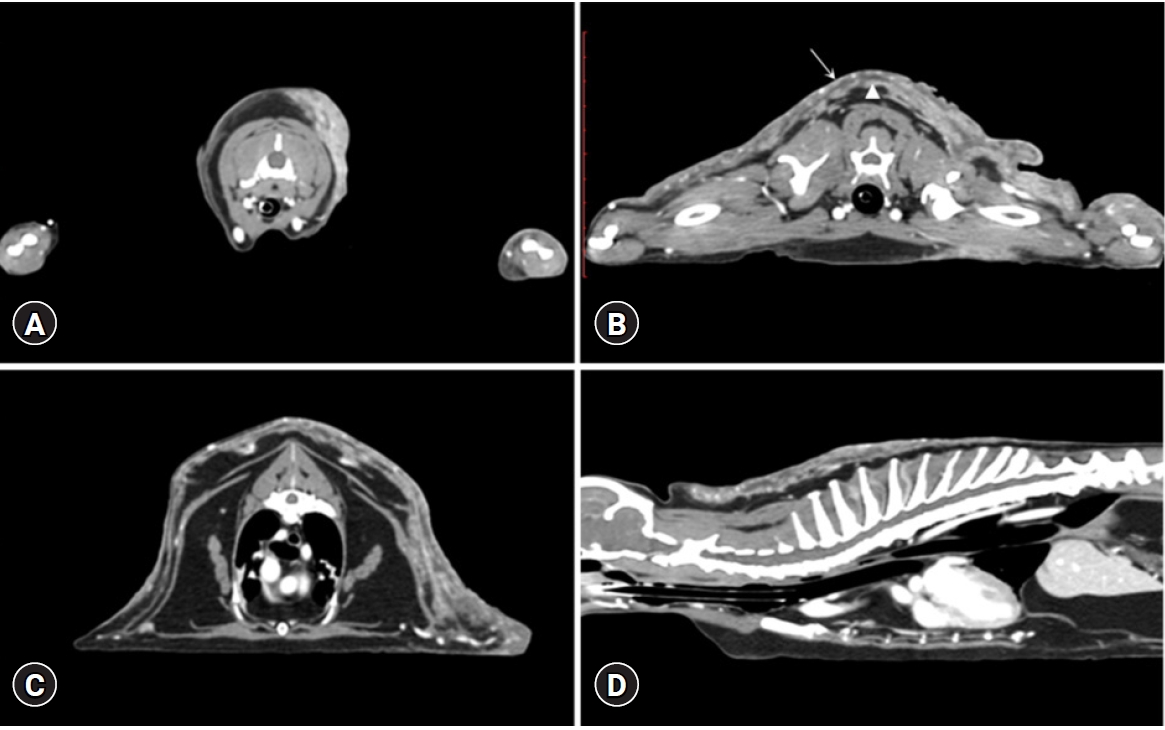

Upon physical examination, ulcerated crust and erythema with numerous skin nodules were observed from the forelimbs to the craniodorsal trunk (

Fig. 1). The nodular masses were firm and fixed under the skin, and the lesions expanded bilaterally to the shoulder area and forelimb. However, a 160 multi-slice computed tomography (CT, Aquilion Lightning 160; Canon Medical Systems, Japan) scan revealed heterogeneous contrast enhancement and extended dorsally from the 1st cervical vertebrae to the 12th thoracic vertebrae level (

Fig. 2). A diffuse, irregularly margined, soft tissue attenuated lesion in the cutaneous layer, superficial fascia, and subcutaneous layer was also detected. No regional or distant lymph node enlargement was identified on either physical examination or CT scan.

Skin cytology, biopsy, and comprehensive laboratory analysis were performed. The results revealed normocytic normochromic mild non-regenerative anemia (red blood cell counts of 5.26 ├Ś 10

6/╬╝L [reference interval {RI}, 6.54-12.2 ├Ś 10

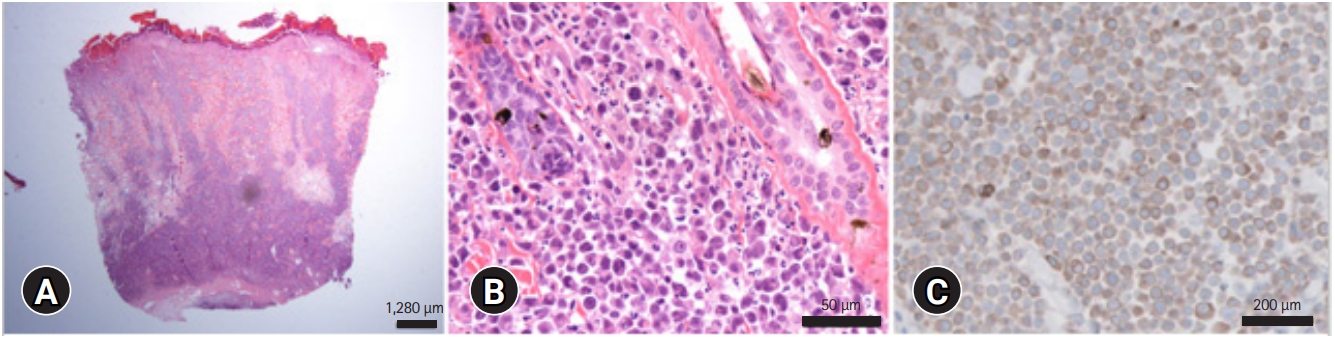

6/╬╝L]; a packed cell volume of 24% [RI, 30.3%-52.3%]; hemoglobin levels of 7.3 g/dL [RI, 9.8-16.2 g/dL]). Paraneoplastic hypercalcemia (ionized calcium level of 1.53 mmol/L [RI, 1.11-1.38 mmol/L]) and decreased blood urea nitrogen (11 mg/dL; RI, 16-36 mg/dL) and serum creatinine (0.7 mg/dL; RI, 0.8-2.4 mg/dL) concentrations as consequences of polyuria secondary to hypercalcemia were observed. Feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus infections were excluded using the feline Triple SNAP test kit (IDEXX, USA). Skin cytology demonstrated a distinctive cytological pattern with a dominance of rounded cells with multilobulated nuclei and moderately basophilic cytoplasm. The nucleus was three times larger than erythrocytes and was anisokaryotic, anisocytic, and binucleated, which met the malignancy criteria. Skin biopsy was performed from three different sites of the left and right scapular lesions using 2 mm-punch biopsy. Histopathological examination of the biopsied sample revealed a non-encapsulated neoplasm comprising a tightly packed sheet of round cells in the dermis and underlying subcutis, with no evidence of epitheliotropism of the neoplastic cells. The neoplastic cells ranged from 9 to 13 ╬╝m in diameter and contained moderate amounts of amphophilic cytoplasm. The nuclei were rounded, had coarsely clumped chromatin, and contained one to several prominent nucleoli. Multiple areas of necrosis were observed throughout the neoplasm. The neoplastic cells stained strongly positive for CD3 but not for Pax5 (

Fig. 3). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of NECL with diffuse large T-cell type was made. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy were suggested; however, the owner chose palliative treatment such as antibiotics, corticosteroids, and bisphosphonate, but it was not responsive. The disease progressed rapidly for 2 weeks after the initial diagnosis, and the owner elected humane euthanasia.

Cutaneous lymphoma is rarely reported and constitutes 0.2% to 3.0% of the feline lymphomas [

6]. ECL is characterized by T cells with an affinity for the epidermis and adnexal epithelium, whereas NECL is of B-or TŌĆÉcell origin and is characterized by neoplastic lymphocytes predominantly in the dermis and subcutis [

1,

5,

7]. Although it is known that NECL is more common in feline cutaneous lymphoma [

7], but most documents are ECL in cats [

4,

8]. The etiology of NECL remains unclear; however, chronic inflammation, prior surgery, trauma, metallic orthopedic implants, and viral infection have been suggested to be risk factors for its development [

5,

6]. Recently, the following feline NECL subgroups have been acknowledged: cutaneous lymphoma at injection sites [

9], tarsal lymphoma [

1], and NECL associated with a fracture site [

6]. They all lack epitheliotropism, and their clinical and pathological features are unique disease entities.

The epitheliotropic and non-epitheliotropic forms can have similar clinical appearances. The lesions may be solitary or diffuse and are often described by various manifestations such as erythematous spots, alopecia, scales, skin nodules, or ulcerative plaques [

5,

7]. The period of existence of the lesion before diagnosis varies from case to case: the lesions can last up to 2 years in NECL [

10], and the lesion progressed rapidly and worsened within 2 months in this case. On gross examination, the lesions were limited to the neck, shoulder, and forelimbs; however, the expanded lesions were visualized from the caudal aspect of the occipital bone to the level of the 12th thoracic vertebrae cutaneous and subcutaneous layers based on CT scanning.

CT has been useful for staging, treatment planning, and prognostication in humans with cutaneous lymphoma [

11-

13]. In the present case, non-epithelial large cell lymphoma was confirmed only in the dermis and subcutis on histological evaluation; however, the CT scan confirmed the presence of a lesion in the cutaneous layer, superficial fascia, and subcutaneous layer despite the ultra-high-resolution CT system. This finding may reflect the limitations of CT examination in the identification of subtle changes in cutaneous lymphoma. Positron emission tomography/CT can be used to evaluate the tumor depth/thickness and biological activity of cutaneous lymphomas in dogs [

13] and humans [

14]. Moreover, the treatment method can be modified according to the results, and ultimately, prognostic evaluation can be applied in humans [

14]. Further research should be conducted to expand the clinical application of CT scanning as a diagnostic and prognostic modality for cutaneous lymphoma in cats.

Owing to the limited number of studies reported to date, no specific treatment regimen has been determined to be optimum for feline cutaneous lymphoma [

3,

6,

10]; chemotherapy, surgical excision, and radiation can be considered [

7]. Currently, the most promising treatment for canine cutaneous lymphoma is lomustine [

3], which can also be used for feline ECL [

2] and NECL [

10]. In a previous report [

10], a cat with NECL achieved complete remission 3 months after lomustine treatment; however, the duration of the remission period is unknown because the patient died 2 months later for other reasons. However, treatment could not be initiated in this case as the owner elected humane euthanasia.

The prognosis of feline NECL is worse than that of ECL. The median survival time reported in the literature is 10.25 months for feline ECL [

3] and 190 days for feline NECL [

1]. Therefore, histopathological subclassification is essential. Further research on the clinical application of various treatments and the analysis of prognosis should be conducted in the future.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print